Genetic Testing and Genetic Expression Profiling in Patients With Cutaneous Melanoma - CAM 255

Description

Cutaneous melanoma is a common and serious form of skin cancer. Diagnosis of this type of cancer often involves visual examination of the skin by a dermatologist; however, due to the various presentations of nodules, it can be difficult to properly recognize a melanoma case. Although several visual systems have been developed to assist in diagnosis (such as the ABCDE system for signature features), a biopsy is often performed to diagnose a case (Swetter, 2021). Genetic testing (particularly gene expression panels) is being explored to assist in diagnosing these cases without a biopsy (Bollard et al., 2021).

Another application of genetic testing in cutaneous melanoma is for “targeted testing”. Certain genetic mutations can lead to better patient response to particular treatments, and it is therefore clinically useful to identify these mutations to help guide selection of the most appropriate therapy.

REGULATORY STATUS

A search of the FDA database on 11/12/2020 using the term “BRAF” yielded 6 results and a search using the term “melanoma” yielded 9 results. Additional tests may be considered laboratory developed tests (LDTs); developed, validated and performed by individual laboratories. LDTs are regulated by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) as high-complexity tests under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA’88). As an LDT, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has not approved or cleared this test; however, FDA clearance or approval is not currently required for clinical use.

The FDA-approvals for all the BRAF-targeted therapies include the requirement that BRAF mutation testing be performed by an FDA-approved test.

On Aug. 17, 2011 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced the approval of Zelboraf (vemurafenib) for unresectable or metastatic melanoma with oncogenic BRAF mutation (V600E). The Cobas® 4800 BRAF V600 Mutation Test was approved as the companion diagnostic for vemurafenib (Bollag et al., 2012).

Dabrafenib was FDA-approved in May 2013 for the treatment of patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation, as detected by an FDA-approved test. Dabrafenib is specifically not indicated for the treatment of patients with wild-type BRAF melanoma (Tafinlar [dabrafenib], Jan 2014).

Trametinib was FDA-approved in May 2013 for the treatment of patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma with BRAF V600E or V600K mutations, as detected by an FDA-approved test. Trametinib is specifically not indicated for the treatment of patients previously treated with BRAF inhibitor therapy (GlaxoSmithKline. Mekinist Aug 2014).

The companion diagnostic test coapproved for both dabrafenib and trametinib is the THxID™ BRAF Kit manufactured by bioMérieux. The kit is intended “as an aid in selecting melanoma patients whose tumors carry the BRAF V600E mutation for treatment with dabrafenib and as an aid in selecting melanoma patients whose tumors carry the BRAF V600E or V600K mutation for treatment with trametinib” (Genentech, Inc. Zelboraf® March, 2014).

The FDA approved the use of the Oncomine Dx target test NGS panel for somatic or germline variants, which includes the BRAF V600E mutation for consideration with dabrafenib therapy as one of the gene variants (Life Technologies Corporation, approved in June 2017).

The FDA approved the FoundationOne CDx NGS panel in November 2017, which does include both the V600E and V600K mutation for possible dabrafenib or vemurafenib therapy (Foundation Medicine, Inc.).

The FDA approved the use of Therascreen BRAF V600E RGQ PCR Kit in April 2020, a real time PCR test that detects BRAF V600E mutations. The Therascreen BRAF V600E RGQ PCR Kit is for use on the Rotor-Gene Q MDx (US) instrument.

Related Policies

20408 Genetic Testing for Lynch Syndrome and Other Inherited Colon Cancer Syndromes

Policy

- For individuals with stage III or stage IV melanoma, testing of tumor tissue for BRAF V600, KIT, and NRAS mutations is considered MEDICALLY NECESSARY prior to the initiation of molecular-targeted treatment.

- Unless required to guide systemic therapy, BRAF, KIT, and NRAS testing of the primary cutaneous melanoma is considered NOT MEDICALLY NECESSARY.

- For individuals who have been adequately counseled on the interpretation of positive and negative results, risk assessment of a suspicious primary melanocytic skin lesion using the DermTech Pigmented Lesion Assay (PLA) is considered MEDICALLY NECESSARY to help inform a biopsy decision when ALL of the following conditions are met:

- When lesion size is 5 – 19 mm;

- When the lesion meets 1 or more ABCDE criteria (Asymmetry, Border, Color, Diameter, Evolving);

- When the lesion is located where the skin is intact (i.e., non-ulcerated or non-bleeding lesions) and free of psoriasis, eczema, or similar skin conditions;

- When the lesion does not contain a scar;

- When the lesion has not been previously biopsied;

- When the lesion is not already clinically diagnosed as benign or melanoma;

- When the lesion is NOT located on the palms of hands, soles of feet, nails, mucous membranes, or hair covered areas that cannot be trimmed.

The following is considered NOT MEDICALLY NECESSARY due to a lack of available published scientific literature confirming that the test(s) is/are required and beneficial for the diagnosis and treatment of a patient’s illness.

- In all other situations not addressed above, including but not limited to decision DX melanoma, genetic expression profiling tests for cutaneous melanoma is considered NOT MEDICALLY NECESSARY.

- In other forms or stages of melanoma, testing for BRAF V600, KIT, NRAS, and other mutations is considered NOT MEDICALLY NECESSARY.

Note: For 5 or more gene tests being run on the same platform, such as multi-gene panel next generation sequencing, please refer to CAM 235 Reimbursement Policy.

Rationale

Melanoma is particularly lethal and aggressive with the ability to metastasize to any organ (Leong et al., 2011). Cutaneous tumors as little as 1 mm in thickness are capable of lymph node metastasis (Stage III), resulting in a significant decrease in the 5-year survival rate from 90% to 56% (Yee et al., 2005). If the cancer has spread beyond the lymph nodes (Stage IV), an even more dramatic decrease in 5-year survival to 15% will occur (Grossmann et al., 2012).

BRAF, KIT, PIK3CA and NRAS mutations are commonly seen in melanoma cases (Alrabadi et al., 2019; Lokhandwala et al., 2019) with an estimated 50% of melanomas exhibiting the BRAF V600E mutation (Burjanivova et al., 2019). BRAF is a member of the RAF family of protein serine/threonine kinases (ARAF, BRAF, CRAF) that is activated by Ras proteins during intracellular signaling cascades. Mutations in BRAF appear to be the most common genetic alteration in melanoma (Hocker & Tsao, 2007) and occur more frequently in melanoma than lung, colon, and ovarian carcinoma (Grossmann et al., 2012). More than 30 mutations of the BRAF gene associated with human cancers have been identified (Siroy et al., 2015). In 90% of cases, thymine is substituted with adenine at nucleotide 1799. This leads to valine (V) being replaced by glutamate (E) at codon 600 (now referred to as V600E) in the kinase domain (Tan et al., 2008). Importantly, BRAF activating mutations occur in up to 80% of benign nevi or moles and, therefore, cannot be used to distinguish benign from malignant melanocytic lesions (Grossmann et al., 2012; Poynter et al., 2006).

Table 1. Frequency of Melanoma Subtypes with Activating Genetic Alterations in BRAF and KIT (taken from (Grossmann et al., 2012)).

|

Aberration |

Cutaneous − CSD |

Cutaneous + CSD |

ALM |

MM |

|

BRAF mutation |

53% |

8% – 11% |

10% |

15% |

|

KIT mutation; amplification |

0 |

17% |

11% – 38%; 19% – 27% |

6% – 19%; 20% – 33% |

A variety of methods are utilized for BRAF and KIT mutational analysis testing in melanoma, which has resulted in no standardized procedures for testing. Because numerous techniques are available and updated methods continue to be released, labs have been reluctant to switch BRAF platforms to accommodate one specific drug for one disease (Grossmann et al., 2012). Current BRAF genetic testing methods include BRAF V600E by real-time PCR, BRAF V600E mutation only by Sanger sequencing, BRAF full gene sequence analysis, and BRAF next generation sequencing (CMGL, 2014).

However, a recent study found good overall compliance of labs with the College of American Pathologists (CAP) (Cree, 2014) and National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for molecular diagnosis of tumors (Volmar et al., 2015) despite not using the specific FDA-approved test.

Table 2. Molecular Testing Adherence to NCCN Guidelines (taken from Volmar et al., 2015)

|

|

All Institutions Percentiles |

|||||

|

n |

10th |

25th |

Median |

75th |

90th |

|

|

Retrospective study (lung, colorectal, melanoma) |

||||||

|

Percentage of tests that strictly meet the guideline |

26 |

32.6 |

64.7 |

70.9 |

82.7 |

89.7 |

|

Percentage of tests that at least loosely meet the guideline |

26 |

57.4 |

90.7 |

95.1 |

98.9 |

100.0 |

|

Prospective study (all case type) |

||||||

|

Percentage of tests that strictly meet the guideline |

23 |

20.0 |

31.4 |

53.3 |

66.7 |

70.5 |

|

Percentage of tests that at least loosely meet the guideline |

23 |

75.0 |

87.0 |

94.3 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

Genetic testing is important to determine the most efficient treatment method for a melanoma patient. Despite the high frequency in nevi, the role of BRAF mutations in oncogenesis is well established (Davies & Gershenwald, 2011) and has been confirmed in clinical trials (Flaherty et al., 2010). The remarkable efficacy of BRAF inhibitors led to the accelerated approval of vemurafenib for unresectable and metastatic melanoma. Importantly, BRAF mutation testing is warranted for determining therapeutic eligibility as selective BRAF inhibitors pose significant risk of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and have the potential to increase disease progression in BRAF wild type (mutation negative) tumors (Grossmann et al., 2012).

Historically, systemic therapy for metastatic melanoma provided very low response rates and little to no benefit in overall survival (Atkins et al., 2000; Tsao et al., 2004). However, this is beginning to change. For example, researchers have now identified that those with the BRAF V600 mutation are able to obtain both immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy and other targeted therapies for an improved overall treatment regimen (Ghate et al., 2019). Moreover, the immune-boosting anti-CTLA-4 antibody ipilimumab (Hodi et al., 2010) and testing and development of small molecule kinase (KIT and BRAF) inhibitors have yielded improvements in long-term survival for melanoma patients (Davies & Gershenwald, 2011; Ribas & Flaherty, 2011; Woodman & Davies, 2010).

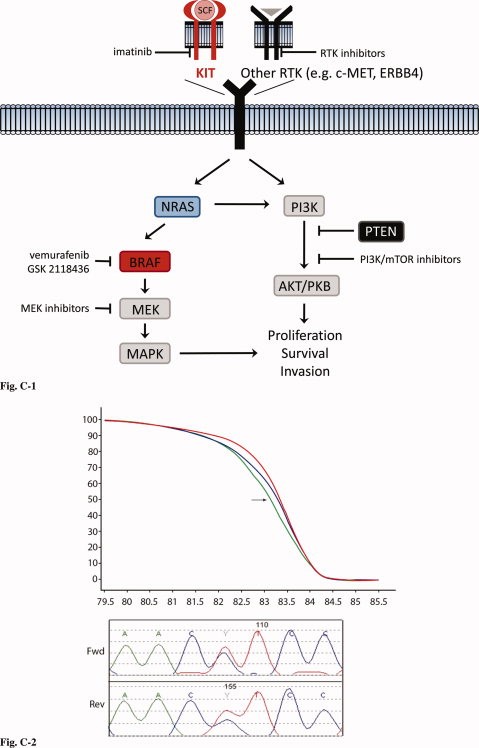

Figure 1: Imatinib and RTK Inhibitor Pathways for Melanoma Treatment (image taken from (Grossmann et al., 2012).

Clinical Utility and Validity

Burjanivova et al. (2019); Corean et al. (2019); McEvoy et al. (2018) analyzed a total of 113 samples from patients with malignant melanoma; the authors state, “The aims of our study were to detect BRAF V600E mutations within circulating cell-free DNA in plasma ("liquid biopsy") by a droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) method.” A BRAF V600E mutation was identified in 37/113 samples, showing that this method is “highly sensitive” in the detection of BRAF V600E mutations and may be used for both mutation detection and treatment monitoring (Burjanivova et al., 2019). A second team of researchers also used ddPCR to identify melanoma mutations including BRAF, NRAS, and TERT; results were compared to both Sanger sequencing and pyrosequencing methods (McEvoy et al., 2018). Overall, ddPCR was found to be more sensitive in detecting mutations than the aforementioned testing methods with an increased sensitivity “more apparent among tumors with <50% tumor cellularity” (McEvoy et al., 2018).

O'Brien et al. (2017) analyzed samples to determine if BRAF mutation identification by immunohistochemistry was a suitable alternative to PCR. 132 patients were included in this study, and the anti-BRAF V600E VE1 clone antibody was used for immunohistochemistry detection. A sensitivity of 86.1% and specificity of 96.9% was shown with the anti-BRAF V600E VE1 clone antibody; “The concordance rate between PCR and immunohistochemical BRAF status was 95.1% (116/122)” (O'Brien et al., 2017). As both methods were in high agreement, immunohistochemistry may be a viable alternative to PCR for BRAF mutation testing.

Corean et al. (2019) utilized several different techniques on metastatic melanoma samples, including bone marrow morphology, histology, immunophenotyping, molecular genetic testing and BRAF V600E immunohistochemistry. BRAF immunohistochemistry was detected in two patients, and molecular testing confirmed these results; researchers then stated that “BRAF V600E immunohistochemistry is useful as a surrogate marker of molecular results,” once again highlighting the fact that immunohistochemistry may be a viable alternative for BRAF mutation testing (Corean et al., 2019).

Available BRAF tests and analytical sensitivities:

- “The BRAF V600E by real-time PCR test uses a TaqMan® Mutation Detection Assay to detect the V600E mutation in exon 15 of BRAF in tumor (somatic) cells. The sensitivity of the TaqMan assay is ~ 0.1% mutant DNA in a wild-type background. Poor DNA quality, insufficient DNA quantity or the presence of PCR inhibitors can result in uninterpretable or (rarely) inaccurate results.

- The BRAF (V600E) mutation only by Sanger sequencing uses a DNA-based PCR-sequencing assay to detect the V600E in exon 15 of BRAF. The limit of detection for Sanger sequencing is > 20% mutant DNA in a wild-type background.

- The BRAF full gene sequence analysis test uses a DNA-based PCR-sequencing assay to detect point mutations in the coding sequence and intron/exon boundaries of the BRAF gene. The sensitivity of DNA sequencing is over 99% for the detection of nucleotide base changes, small deletions and insertions in the regions analyzed. Rare variants at primer binding sites may lead to erroneous results. The limit of detection for Sanger sequencing is > 20% mutant DNA in a wild-type background” (CMGL, 2014).

- The BRAF NGS with TruSeq had sensitivity of over 99% (Froyen et al., 2016).

Colombino et al. (2020) compared BRAF mutation testing performed with conventional nucleotide sequencing approaches (Sanger sequencing and pyrosequencing) with real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) or next-generation sequencing (NGS) assays to assess the levels of concordance between these various techniques. 319 tissue samples were analyzed and initially screened with conventional approaches. The initial screen found pathogenic BRAF mutations in 144 (45.1%) cases. RT-PCR (Idylla™ BRAF mutation assay) detected 11 (16.2%) and 3 (4.8%) additional BRAF mutations after Sanger sequencing and pyrosequencing, respectively. NGS detected one additional BRAF-mutated case (2.1%) among 48 wild-type cases previously tested with pyrosequencing and RT-PCR. According to the data, RT-PCR is more accurate than both Sanger sequencing and pyrosequencing in detecting BRAF mutations. Overall, RT-PCR had a good concordance with the other tests; 60/61 (98.4%) RT-PCR tests confirmed the presence of the same BRAF mutation identified by the sequencing assay. "Real-time PCR is a rapid method which achieves the same maximum level of sensitivity of NGS (up to 98%), without requiring particular skills” (Colombino et al., 2020). Although NGS can provide a detailed evaluation with a high diagnostic sensitivity, the interpretation of sequencing data may be complex, requires a high level of expertise, and makes it difficult to apply in the clinical practice. "Sanger-based direct sequencing achieves the highest specificity (100%) and can detect all sequence mutations in BRAF exons, but it presents the lowest diagnostic sensitivity (80% – 85%). Pyrosequencing is a simple-to-perform method and provides a good level of sensitivity (92% – 95%), but it does not achieve a complete mutation coverage specificity (up to 90%) (Colombino et al., 2020).” According to the author, “[RT-PCR and NGS] improved the diagnostic accuracy of BRAF testing via the detection of additional BRAF mutations in a subset of false-negative cases previously tested with Sanger sequencing or pyrosequencing. In attendance of further confirmations in larger prospectively designed studies, the use of two sensitive molecular methods may ensure the highest level of diagnostic accuracy” (Colombino et al., 2020).

BRAF analysis is an accepted medical practice for patients with unresectable, metastatic stage IV melanoma (NCCN, 2022). However, recent randomized controlled trials have indicated the benefits of expanding BRAF analysis. A study published in The Lancet Oncology by Amaria et al. (2018) compared standard of care in patients with high-risk, surgically resectable melanoma (stage III or IV) to similar patients receiving a regimen of a neoadjuvant plus adjuvant dabrafenib and trametinib. All patients had to be of confirmed BRAF V600E or BRAF V600K status to participate in either the control or experimental groups. In the follow-up (median of 18.6 months), 10/14 (or 71%) of patients in the experimental group remained event-free (i.e., alive without disease progression), whereas 0/7 (0%) of the control group receiving standard of care remained event-free. The authors conclude that the “Neoadjuvant plus adjuvant dabrafenib and trametinib significantly improved event-free survival versus standard of care in patients with high-risk, surgically resectable, clinical stage III – IV melanoma” (Amaria et al., 2018).

Another study published by Zippel et al. (2017) researched the use of perioperative BRAF inhibitors on patients with stage III melanoma. All patients had to be confirmed BRAF V600E to participate in the study. Of the thirteen patients, twelve “patients showed a marked clinical responsiveness to medical treatment, enabling a macroscopically successful resection in all cases;” moreover, “at a median follow up of 20 months, 10 patients remain free of disease” (Zippel et al., 2017). One patient died prior to surgery in this study. The authors conclude that the “Perioperative treatment with BRAF inhibiting agents in BRAFV600E mutated Stage III melanoma patients facilitates surgical resection and affords satisfactory disease free (sic) survival” (Zippel et al., 2017).

Gene Expression Profiling for Diagnosis and Prognosis

Currently, patients presenting with a suspicious pigmented lesion undergo excisional biopsy which is then subjected to histopathologic examination by a pathologist (NCCN, 2022). The majority of melanocytic neoplasms can be accurately classified by this approach; however, in some cases confidently differentiating benign melanocytic nevi from malignant melanoma can be extremely difficult or impossible despite additions to histopathologic assessment, such as the evaluation of Breslow depth (Chiaravalloti et al., 2018; Lee & Lian, 2018). In these cases, even diagnoses from expert pathologists can be discordant (Elmore et al., 2017; Farmer et al., 1996; Gerami et al., 2014) and subject to diagnostic drift (Bush et al., 2015). A number of diagnostic and prognostic genetic tests for melanoma have been developed as ancillary tests to assist in this differentiation and resultant risk stratification (Lee & Lian, 2018), including microRNAs as biomarkers to distinguish between melanomas and nevi (Torres et al., 2019). In particular, gene expression profiling is growing in popularity for the diagnosis and prognosis of cutaneous melanoma. Molecular tests based on gene expression profiling of cutaneous melanoma are commercially available. They include the 23-GEP MyPath Melanoma (Myriad, 2020), 2-GEP Pigmented Lesion Assay (DermTech, 2020a), 31-GEP DecisionDx-Melanoma (Castle_Biosciences, 2020), 11-GEP Melagenix test (NeraCare, 2022), and a clinicopathologic (CP)-GEP model by SkylineDx (SkylineDx, 2020).

Clinical Utility and Validity of Gene Expression Profiling

MyPath Melanoma (Castle Biosciences)

A 23-gene expression profile and algorithm that assigns various weights and thresholds of expression for each gene was developed to differentiate benign melanocytic nevi from malignant melanoma; this gene expression profile and algorithm was determined to have a sensitivity of 89% and specificity of 93% (Clarke et al., 2015). Further, three experienced dermatopathologists validated this method against an independent histopathologic evaluation; a sensitivity of 91.5% and a specificity of 92.5% was determined (Clarke, Flake, et al., 2017). This gene expression profile was developed into a commercial test known as MyPath Melanoma which generates a single numerical score along with a classification of likely malignant, likely benign, or indeterminate, for a given cutaneous lesion. Across various validation studies, MyPath Melanoma has demonstrated a sensitivity in the range of 90% – 94% and a specificity in the range of 91% – 96% (Ko et al., 2017).

MyPath Melanoma correlates closely with long-term clinical outcomes by adding valuable adjunctive information to aid in the diagnosis of melanoma. An examination of the utility of this test (Cockerell et al., 2017) found that the results of this gene expression signature have a significant clinical impact with 71.4% (55/77) of cases changing from pretest recommendations to actual treatment. The majority of changes were consistent with the test result. There was an 80.5% (33/41) reduction in the number of biopsy site re-excisions performed for cases with a benign test result. However, when more challenging samples were included (Minca et al., 2016) with 39 histopathologically unequivocal lesions (15 malignant, 24 benign) and 78 challenging lesions interpreted by expert consensus (27 favor malignant, 30 favor benign, and 21 ambiguous), myPath Melanoma had a lower sensitivity and specificity than fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) (FISH: 69% sensitivity, 91% specificity; myPath; 55% sensitivity, 88% specificity). In the unequivocal group, FISH and myPath score showed 97% and 83% agreement with the histopathologic diagnosis, respectively, with 93% and 62% sensitivity, 100% and 95% specificity, and 80% inter-test agreement. In the challenging group, FISH and the myPath score showed 70% and 64% agreement with the histopathologic interpretation, respectively, with 70% inter-test agreement. The myPath Melanoma testing method may have limited sensitivity in cases of desmoplastic melanoma, a rare fibrosing variant of melanoma (Clarke, Pimentel, et al., 2017). The exclusion of melanocytic neoplasms that did not have a triple concordant diagnosis, and the lowered sensitivity and specificity when these sample types were included may significantly limit the applicability of this test in the most challenging diagnostic circumstances (Lee & Lian, 2018).

In contrast, (Clarke et al., 2020) completed another study that evaluated the accuracy of myPath melanoma in diagnostically uncertain neoplasms. Out of 125 diagnostically “uncertain” cases, myPath melanoma demonstrated a sensitivity of 90.4%. In this study, the test displayed no significant difference in sensitivity between the diagnostically uncertain (equivocal) and unequivocal lesion groups. It is unclear why myPath melanoma would perform better in one population of diagnostically “uncertain” lesions over another, though the authors cite certain limitations of the study. These include reliance on a single diagnostic slide of each biopsy specimen, and lack of access to complete clinical and demographic information (Clarke et al., 2020). Given varying results, further study may be required to develop a consensus on the performance of myPath melanoma.

Pigmented Lesion Assay (PLA) (DermTech)

DermTech has developed a pre-diagnostic quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)-based pigmented lesion assay (PLA) that measures the expression of two genes in the stratum corneum to assist with diagnostic or prognostic information for potential melanoma cases (Varedi et al., 2019). DermTech’s PLA identifies malignant changes on a genomic level that cannot be detected with the human eye; this assay can be used to support clinicians in their decision to biopsy suspicious nevi. This test has the potential to increase the number of early melanomas biopsied and reduce the number of benign lesions biopsied, thereby improving patient outcomes (Ferris et al., 2017). A recent study has given this pigmented lesion assay a sensitivity of 91-96%, a specificity of 69-91%, and a negative predictive value of approximately 99% (Ferris, Rigel, et al., 2019).

To help support clinicians in their decision to biopsy, this noninvasive 2-gene expression assay of the LINC00518 and PRAME genes has been developed for use on adhesive patch biopsies. Skin sampling via an adhesive patch allows for DNA, RNA, skin tissue and microbiome samples to be safely obtained and transported cost effectively by mail at room temperature; skin cells, T-cells, dendritic cells, melanocytes and other types of cells can be analyzed by this method (Yao et al., 2017). The use of an adhesive patch also allows 100% of the lesion’s surface to be sampled, compared to less than 1% – 2% of surgical biopsies (DermTech, 2020b). Further, this technique is a much more cost-effective option. Hornberger and Siegel (2018) report that PLA testing could save approximately $447 per lesion compared to traditional biopsies.

Gerami et al. (2017b) tested the validity of the two-gene panel based on LINC00518 and PRAME on differentiating melanoma from nonmelanoma in a multicenter study across 28 sites in the United States, Europe, and Australia. In a sample of 398 (87 melanomas and 311 nonmelanomas), it was found that this classification method was able to accurately identify melanomas from nonmelanomas with a sensitivity of 91% and a specificity of 69%. Other researchers have determined the utility of this pigmented lesion assay for LINC00518/PRAME expression; using this assay, dermatologists improved their mean biopsy sensitivity from 95.0% to 98.6% (P = .01) and improved their specificity from 32.1% to 56.9% (P < .001) (Gerami et al., 2017a). This result may increase the number of early melanomas biopsied and reduce the number of benign lesions biopsied, thereby improving patient outcomes and reducing health care costs (Ferris et al., 2017). An application study of 381 patients found that the estimated real-world sensitivity of the DermTech PLA was 95% and specificity was 91% (Ferris et al., 2018); overall, 93% of PLA results positive for both LINC00518 and PRAME were diagnosed histopathologically as melanoma. Further, this study was also used to identify if the real-world clinical use of the DermTech PLA could change physician behavior and reduce the overall number of biopsies performed. The PLA identified 51 PLA(+) test results, and 100% of these pigmented skin lesions were biopsied (37% were melanomas). Furthermore, “Nearly all (99%) of 330 PLA(-) test results were clinically managed with surveillance. None of the three follow-up biopsies performed in the following 3 – 6 months, were diagnosed as melanoma histopathologically” (Ferris et al., 2018). The PLA test altered clinical management of pigmented lesions and shows high clinical performance. However, it is uncertain if the negative samples — as determined by the PLA — will remain so, as “we [the authors] cannot rule out that some PLA(−) lesions may not have been adequately reassessed in the follow-up period and we certainly recommend erring on the side of caution and surgically biopsying a lesion in question if additional risk factors, further clinical suspicion, or patient concern mandate such a step” (Ferris et al., 2018).

The PLA test has also been validated against driver mutations in melanoma, including BRAF, NRAS, and TERT. Ferris, Moy et al. (2019) studied the mutation frequency of these genes using samples obtained from the PLA technique (e.g., adhesive patch) in both histopathologically confirmed melanomas (n = 30) and non-melanoma controls (n = 73). “The frequency of these hotspot mutations in samples of early melanoma was 77%, which is higher than the 14% found in nonmelanoma samples (P < 0.0001). TERT promoter mutations were the most prevalent mutation type in PLA-positive melanomas; 82% of PLA-negative lesions had no mutations, and 97% of histopathologically confirmed melanomas were PLA and/or mutation positive” (Ferris, Moy et al., 2019). 86% of the non-melanomas within this validation cohort contained no mutations. The authors next analyzed 519 real-world PLA samples for the same mutations. Similar to the previous validation cohort, 88% of this larger cohort also contained no mutations, indicating that the PLA test can rule out lesions with few mutational risk factors for melanoma.

Another study by Ferris, Rigel et al. (2019) followed up with patients who were given PLA(-) results for a year to determine the utility of this pigmented lesion assay; no lesions biopsied in the twelve month period were given a histopathologic diagnosis of melanoma, highlighting the accuracy of this technique. Further, Brouha et al. (2020) completed a large United States registry study which included the assessment of 3,148 suspicious pigmented skin lesions. All skin lesions were analyzed by PLA and were considered PLA(+) if LINC and/or PRAME was identified. All PLA(+) samples (9.48%) were surgically biopsied and analyzed. The PLA was found to have a negative predictive value > 99% and reduced cost as well as biopsies by 90%; further, “97.53% of PLA(+) lesions were surgically biopsied, while 99.94% of PLA(-) cases were clinically monitored and not biopsied” (Brouha et al., 2020).

Skelsey et al. (2021) further confirmed the “real-world” negative predictive value (NPV) and positive predictive value (PPV) of the PLA, “by following a cohort of 1,233 PLA-negative pigmented lesions for evidence of malignancy for up to 36 months and by re-testing a separate prospective cohort of 302 PLA-negative lesions up to 2 years after initial testing.” Out of this total PLA-negative cohort, 1,233 lesions had a confirmed follow-up evaluation; of these, 10 melanomas were subsequently detected by way of biopsy, resulting in an NPV of 99.2%. Out of 316 PLA-positive cases, 59 were diagnosed as melanoma by histopathology, resulting in a PPV of 18.7% (Skelsey et al., 2021). The PPV achieved through use of the PLA may represent a 5-fold improvement over the current standard according to the test’s developers.

In a continuing medical education series, Skudalski et al. (2022) confirm that the PLA is to be used as a risk stratification aid in determining whether to biopsy a skin lesion. The authors recommend that in the case of a positive PLA result, “biopsy in toto should be performed immediately.” They further comment that after a negative PLA result, clinicians have chosen to follow up within 12 months to further evaluate the skin lesion; however, a biopsy in toto should be considered if a patient remains concerned about a lesion, or if the lesion has evolved (Skudalski et al., 2022).

A recent report by Robinson & Jansen (2020) outlined a proof-of-concept pilot program of remote physician-guided self-sampling (i.e., telehealth administration of the adhesive patch) during the Illinois stay-at-home order of the COVID-19 pandemic. The authors also surveyed skin self-examination (SSE) anxiety as well. Two cohorts were used in this pilot, an experimental group (n = 7), and a randomly selected physician-sampled control case group (n = 10). The authors report that SSE-induced anxiety has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. It should be noted that surveys were administered to much larger groups than those administering self-sampling tests. 258 surveys about SSE anxiety were conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, and 211 surveys during the COVID-19 pandemic. The authors state, “Guided self-sampling led to molecular risk factor analyses in 7/7 (100%) of cases compared to 9/10 (90%) randomly selected physician-sampled control cases. ... Adhesive patch self-sampling under remote physician guidance is a viable specimen collection option” (Robinson & Jansen, 2020).

DecisionDx-Melanoma (Castle Biosciences)

After a melanoma case has been identified, several management approaches may be considered. However, best melanoma management practices are constantly evolving. A common technique to assess the spread of a tumor, such as melanoma, is a sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB). This procedure is used to evaluate whether the cancer has spread beyond the original tumor site and into the lymphatic system. The lymphatic or lymph system transports fluid known as lymph throughout the body; this fluid contains white blood cells which help to fight infections. The lymphatic system also aids in ridding the body of other waste and toxins. The SLNB technique essentially helps the physician to stage the tumor. However, melanoma-related lymph node spread is very complex and is associated with many factors, including age, location, thickness, ulceration, gender, and regression (Ribero et al., 2017).

The DecisionDx-Melanoma test is a gene expression profile (GEP) test that measures the expression of 31 different genes in a tumor tissue sample. This test was designed for cutaneous melanoma patients undergoing or considering SLNB and can help to identify the risk of cancer recurrence or metastasis in stage I – III melanoma (CastleBiosciences, 2020). DecisionDx-Melanoma may help physicians guide treatment options, including whether to perform a SLNB in eligible patients, and what type of follow up treatment is necessary (CastleBiosciences, 2020). After GEP analysis, the DecisionDx-Melanoma provides a score of either Class 1 (low risk) or Class 2 (high risk), as well as A or B scores with “A” reflecting a better outcome and “B” reflecting a worse outcome; this allows physicians to receive final scores of Class 1A, 1B, 2A, and 2B (Gastman, Zager, et al., 2019).

The DecisionDx-Melanoma is performed on tumor tissue biopsies that have been preserved as formalin‐fixed, paraffin‐embedded (FFPE) samples (CastleBiosciences, 2020). Researchers have highlighted that the identification of tissue-based prognostic markers in melanoma has been a challenging obstacle for researchers, as “One major limitation is that most primary melanomas are preserved as formalin‐fixed, paraffin‐embedded (FFPE) samples rather than fresh‐frozen tissues because of the small size of the specimens” (Weiss et al., 2015). High-quality genetic material is more challenging to extract from FFPE samples, and messenger RNA is inconsistent in FFPE samples (Weiss et al., 2015).

Gerami, Cook, Wilkinson et al. (2015) reported on a “prognostic 28-gene signature” for the identification of high-risk cutaneous melanoma tumors; this test accurately predicted metastasis risk in a multicenter cohort of primary cutaneous melanoma tumors by identifying genes that were upregulated in metastatic melanoma but not in primary melanoma. Metastatic risk was predicted with high accuracy in development (ROC = 0.93) and validation (ROC = 0.91) cohorts of primary cutaneous melanoma tumor tissue. The sensitivity was 100% and specificity of 78%; Kaplan–Meier analysis indicated that the 5-year disease-free survival (DFS) rates in the development set were 100% and 38% for predicted classes 1 and 2 cases, respectively (P < 0.0001) (Gerami, Cook, Wilkinson, et al., 2015). A second study by Gerami, Cook, et al. (2015a) found that the gene expression profile was a more accurate predictor than sentinel lymph node biopsy independently, and improved prognostication in combination with sentinel lymph node biopsy. A multi-center study (Zager et al., 2018) validated the prognostic accuracy in an independent cohort of cutaneous melanoma patients and found that the gene expression profile was a significant predictor of recurrence free survival and distant metastasis free survival in univariate analysis (hazard ratio [HR] = 5.4 and 6.6, respectively, P < 0.001 for each); this study also provided additional independent prognostic information to traditional staging which helps to estimate an individual’s risk for cancer recurrence. A prospective evaluation of the gene expression profile’s performance in 322 patients enrolled in two clinical trials found that patient outcomes from the combined prospective cohort supports the gene expression profile’s ability to stratify early-stage cutaneous melanoma patients into two groups with significantly different metastatic risk; further, it was determined that survival outcomes in this real-world cohort are consistent with previously published analyses with retrospective specimens and that gene expression profile testing complements current clinicopathologic features and increases identification of high-risk patients (Hsueh et al., 2017).

The prognostic utility of this test has been measured by Keller et al. (2019); a total of 159 patients participated in this study and were followed up with, on average, 44.9 months after initial testing. Gene expression profiling results helped to categorize patients into two groups: low-risk patients were placed in Class 1, and high-risk patients in Class 2; 117 patients were placed in Class 1 and 42 patients in Class 2 (Keller et al., 2019). Results showed that this gene expression profiling test had great prognostic abilities. “Gender, age, Breslow thickness, ulceration, SNB positivity, and AJCC stage were significantly associated with GEP classification (P < 0.05 for all). Recurrence and distant metastasis rates were 5% and 1% for Class 1 patients compared with 55% and 36% for Class 2 patients. Sensitivities of Class 2 and SNB for recurrence were 79% and 34%, respectively” (Keller et al., 2019).

Podlipnik et al. (2019) also studied the prognostic utility of this test in a similar way: patients were categorized into Class 1 (low risk) and Class 2 (high risk) based on the DecisionDx-Melanoma gene expression profile test results. Results showed that this testing method could correctly identify patients in accordance with the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system for prognostic purposes. “We believe that gene expression profile in combination with the AJCC staging system could well improve the detection of patients who need intensive surveillance and optimize follow-up strategies” (Podlipnik et al., 2019). Similarly, (Hyams et al., 2021) determined that 31-GEP test results influenced the duration and number of follow-up and surveillance events in patients with a diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma. “High-risk” (class 2) patients received increased management compared to low-risk (class 1) patients; 98% of those identified as high-risk received surveillance intensity equivalent to that given for higher stage (IIB – IV) patients (Hyams et al., 2021). Hence, appropriate use of the 31-GEP may influence the course of care for patients with a diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma.

Berman et al. (2019) gathered an expert panel of nine dermatologists/dermatologic surgeons/ dermatopathologists and completed 29 clinical scenarios in which gene expression tests could be used appropriately; several gene expression profiling (GEP) tests were used including a 2-GEP assay, 23-GEP assay and 31-GEP assay. “The 2-GEP assay for melanoma diagnosis received 1 B-strength and 6 C-strength recommendations. The 23-GEP diagnostic test received 1 A-strength, 3 B-strength, and 4 C-strength recommendations. The 31-GEP prognostic assay received 1 A-strength, 7 B-strength, and 6 C-strength recommendations;” this report shows that the 31-GEP assay received the highest overall recommendations by the expert panel (Berman et al., 2019).

Another study reported that the 31-GEP was validated in almost 1,600 patients “as an independent predictor of risk of recurrence, distant metastasis and death in Stage I-III melanoma and can guide SLNB decisions in patient subgroups, as demonstrated in 1421 patients;” further, an appropriate 31-GEP testing population was identified and concluded that it is best used on patients with cutaneous melanoma tumors greater than or equal to 0.3 mm thick (Marks et al., 2019). However, this study reports several conflicts of interest that are important to note as multiple authors are employees at Castle Biosciences, Inc., and one author is a consultant and speaker for the company (Marks et al., 2019).

Dubin et al. (2019) also published an article that reviewed seven studies aiming to validate 31-GEP testing for cutaneous melanoma patients; the authors found “the 31-GEP test to be particularly useful for patients with invasive melanoma or older patients with T1/T2 melanomas. For patients with invasive melanoma, the results of the molecular test may help guide the frequency of skin examinations and utilization of SLNB or imaging following diagnosis.” However, conclusions stated that differences were identified between the author’s findings and official published guidelines which “may be attributed to chronological issues, as many of the studies were not yet published when the aforementioned organizations conducted their reviews”; the authors further recognized that “There was also difficulty in applying the National Comprehensive Cancer Network criteria to this prognostic test, as their guidelines were intended for evaluation of predictive markers. Nevertheless, based upon the most current data available, integration of the 31-GEP test into clinical practice may be warranted in certain clinical situations” (Dubin et al., 2019). Once again, relevant conflicts of interest for this study include that two authors serve on the advisory board of Castle Biosciences (Dubin et al., 2019).

Greenhaw et al. (2020) completed a meta-analysis of the DecisionDx-Melanoma 31-GEP prognostic test in a total of 1,479 patients. This meta-analysis included participants from three different studies. The patient analysis showed that the five-year recurrence and distant metastasis-free survival rate for Class 1A patients was 91.4% and 94.1% respectively and were 43.6% and 55.5% for Class 2B patients. The 31-GEP was then used to estimate the likelihood of recurrence and distance metastasis. The GEP test exhibited a sensitivity of 76% for each endpoint, showing consistency and accuracy for the identification of at increased risk of metastasis (Greenhaw et al., 2020).

Hsueh et al. (2021) evaluated a 31-gene expression profile test in a prospective analysis of cutaneous melanoma outcomes for prognostic value. Two studies “INTEGRATE” and “EXPAND” were initiated with 323 patients with stage I-III cutaneous melanoma. The authors recorded 3-year recurrence-free survival (RFS), distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS), and overall survival (OS). Results indicated the “31-GEP was significant for RFS, DMFS, and OS in a univariate analysis and was a significant, independent predictor of RFS, DMFS, and OS in a multivariate analysis.” Authors overall concluded that “Combining 31-GEP results and AJCC staging enhanced sensitivity over each approach alone” (Hsueh et al., 2021).

Gastman, Zager et al. (2019) used the commercially available DecisionDx-Melanoma to classify the recurrence risk of 157 cutaneous melanoma tumors as low-risk Class 1 or high-risk Class 2; a total of 110 of these patients had a SLNB. Results showed that the 31-GEP was able to identify 74% of patients who developed distant metastases; further, 88% of patients who were categorized as Class 2 died from the disease over a 5-year period (Gastman, Zager, et al., 2019).

Gastman, Gerami, et al. (2019) used data from three previous studies with GEP-results, totaling 690 participants. Analyses were performed and showed that 70% of patients with SLNB negative results (SLN-negative) were categorized as Class 2 and exhibited metastasis. Both the DecisionDx-Melanoma 31-GEP class 2B and SLN positivity were shown to be independent predictors of cancer recurrence in patients with T1 tumors (Gastman, Gerami et al., 2019).

Zager et al. (2018) evaluated the DecisionDx-Melanoma 31-GEP test’s prognostic accuracy in a multi-center study of 523 patients with cutaneous melanoma; all participants were classified as Class 1 (low risk) or Class 2 (high risk). The molecular classification from the GEP test was correlated to the clinical outcome of each patient, as well as the AJCC staging criteria. The authors note that “The 5-year RFS [recurrence free survival] rates for Class 1 and Class 2 were 88% and 52%, respectively, and DMFS [distant metastasis-free survival] rates were 93% versus 60%, respectively (P < 0.001). The GEP was a significant predictor of RFS and DMFS in univariate analysis (hazard ratio [HR] = 5.4 and 6.6, respectively, P < 0.001 for each), along with Breslow thickness, ulceration, mitotic rate, and sentinel lymph node (SLN) status” (P < 0.001 for each) (Zager et al., 2018). This study showed that the GEP was able to assist with prognostic information to estimate cancer recurrence.

Hsueh et al. (2017) completed a multi-registry study to analyze the survival estimate of a group of 322 cutaneous melanoma patients with the 31-GEP test. The median follow-up time for event-free patients was 1.5 years. The authors note that “1.5-year RFS, DMFS, and OS [overall survival] rates were 97 vs. 77%, 99 vs. 89%, and 99 vs. 92% for Class 1 vs. Class 2, respectively” (p < 0.0001 for each) (Hsueh et al., 2017). These results support the idea that the 31-gene GEP can accurately classify cutaneous melanoma patients into two groups based on significantly different metastatic risk.

Gerami, Cook, et al. (2015b) assessed the prognostic accuracy of the 31-GEP compared to SLNB tests in a multicenter cohort of 217 individuals. End-point analyses include disease-free, distant metastasis-free, and overall survivals. Results showed that the “GEP outcome was a more significant and better predictor of each end point in univariate and multivariate regression analysis, compared with SLNB” (P < .0001 for all); further, the combination of both GEP and SLNB improved prognostication (Gerami, Cook, et al., 2015b). Finally, for patients who received a high-risk GEP result and a negative SLNB, Kaplan-Meier 5-year disease-free was 35%, distant metastasis-free was 49% and overall survival was 54%. This study showed that the 31-GEP could accurately predict metastatic risk in patients undergoing SLNB.

Litchman et al. (2020) published a systematic review and meta-analysis of GEP for primary cutaneous melanoma prognosis. The authors included 29 articles within the systematic review. Even though nine unique gene signatures were reported, the authors decided to focus on the 31-gene GEP test by Castle Biosciences (and the six studies on the prognostic validity) due to the heterogeneity between the gene signatures and the lack of reported studies for some of the other tests. They note “significant heterogeneity between studies.” They report a pooled hazard ratio (HR) for recurrence-free survival (RFS) of 7.22 (95% CI, 4.75 – 10.98). Likewise, the pooled HR for distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) was 6.62 (95% CI, 4.91-8.91), and the pooled HR for overall survival was 7.06 (95% CI, 4.44 – 11.22). The authors state, “A high-risk GEP result may appropriately influence a clinician to refer a patient for this [SLNB] procedure. Current NCCN guidelines suggest that patients with a 5% risk of positive SLNB should undergo SLNB. Although GEP testing may help stratify patient risk for SLNB positivity, GEP is not currently recommended to replace SLNB as evidenced by the results of this review. … In conclusion, the findings of this review have clinical implications for patients with melanoma to better assess their prognosis leading to more effective management of their disease. The results of this study may be useful when deciding to offer GEP testing to primary cutaneous melanoma patients” (Litchman et al., 2020).

Mirsky et al. (2018) studied the impact of the 31-GEP test on management decisions made by physician assistants (PA) and nurse practitioners (NP). A total of 164 Pas and NPs attending a national dermatology conference completed an online survey on the potential impact of the 31-GEP test. The authors note that “In the majority of cases, a lower risk 31-GEP test result led to a statistically significant decrease in the proportion of PA/NPs who would recommend SLNBx [sentinel lymph node biopsy, SLNB], imaging, or quarterly follow-up. Conversely, a higher risk 31-GEP result significantly altered management toward increased intensity (more recommendations for SLNBx, imaging, or quarterly follow-up) in all cases” (Mirsky et al., 2018). However, these are hypothetical management scenarios.

Schuitevoerder et al. (2018) completed a retrospective review of 91 patients seen between September 2015 and August 2016 to determine the impact of the GEP results on patients with clinically node negative cutaneous melanoma, as determined after SLNB. Of 91 patients, 38 were identified as stage I, 42 were identified as stage II, 10 were identified as stage III, and 1 was identified as stage IV. GEP results were found to be significantly associated with the management of both stage I and stage II patients; a difference was not found in the follow-up in stage III of IV results (Schuitevoerder et al., 2018). Further, a Class 2 GEP result led to more aggressive disease management.

Svoboda et al. (2018) researched the factors that cause a clinician to utilize the 31-GEP. A survey was completed by 181 dermatologists attending a national conference. A majority of clinicians stated that they would use the 31-GEP test if the tumor had a Breslow thickness ≤ 0.5mm. Further, the presence of ulceration also showed a statistically significant increase in potential 31-GEP use. Finally, “A negative SLN was only associated with a statistically significant increase in the percentage of clinicians who would recommend the test for the thinnest (0.26 mm) tumors (22% to 34%, P = 0.033)” (Svoboda et al., 2018). The authors note that ulceration was the most important factor in this group of dermatologists to influence the use of the 31-GEP.

Dillon et al. (2018) studied the impact of the 31-GEP on clinical management of melanoma patients. Pre- and post-test recommendations were assessed before and after 31-GEP results were provided to physicians at 16 dermatology, surgical, or medical oncology centers. A total of 247 melanoma samples were included in this study. Results showed that after 31-GEP results were obtained, post-test management plans changed for 49% of cases (36% class I and 85% class II cases). “GEP class was a significant factor for change in care during the study (p < 0.001), with Class 1 accounting for 91% (39 of 43) of cases with decreased management intensity, and Class 2 accounting for 72% (49 of 68) of cases with increases” (Dillon et al., 2018). These results showed that the 31-GEP did affect the clinical management of cutaneous melanoma cases.

Berger et al. (2016) studied the clinical impact of the 31-GEP test on 156 cutaneous melanoma patients. A total of 42% of the participants were identified as stage I, 47% were identified as stage II, and 8% were identified as stage III. The 31-GEP classified 61% of participants as Class 1 and 39% of participants as Class 2. After 31-GEP results were received, 53% of patients experienced changes in disease management, and “The majority (77/82, 94%) of these changes were concordant with the risk indicated by the test result (p < 0.0001 by Fisher’s exact test), with increased management intensity for Class 2 patients and reduced management intensity for Class 1 patients” (Berger et al., 2016). These results show that the 31-GEP did have a clinical impact on cutaneous melanoma disease management.

However, a follow up study (Cook et al., 2018) on the analytic validity of DecisionDx found inter assay concordance of 99% and inter instrument concordance of 95% with a technical success of 98%, demonstrating that DecisionDx-Melanoma demonstrates strong reproducibility between experiments and has high technical reliability on clinical samples. It may be a useful diagnostic and prognostic adjunct in the workup of thin to intermediate thickness melanomas, especially in counseling patients who are candidates for sentinel lymph node biopsy. However, this assay has not been tested on the full spectrum of histologic subtypes of melanoma, and it is unclear how these results should be integrated into current staging criteria (Lee & Lian, 2018).

Moreover, Marchetti et al. (2020) completed an assessment of the prognostic accuracy of the 31-GEP in patients that had cancer labeled as AJCC state I or II disease. Patients with localized melanoma were included from external validation studies, and after exclusion criteria, there were 7 studies analyzed. Five of these studies used the DecisionDx-Melanoma test. Authors looked at the results of the 7 included studies (1450 study participants) and concluded that the performance of both GEP tests (MelaGenix and DecisionDx-Melanoma) varied by AJCC stage. “For patients tested with DecisionDx-Melanoma, 623 had stage 1 disease (6 true-positive ([TP], 15 false-negative, 61 false-positive, and 541 true-negative [TN] results) and 212 had stage II disease 959 TP, 13 FN, 78 FP, and 62 TN results). Among patients with recurrence, Decision Dx-Melanoma correctly classified 29% with stage I disease and 82% with stage II disease. Among patients without recurrence, the test correctly classified 90% with stage I disease, and 44% with stage II disease.” The overall conclusion by authors was that the prognostic ability was “poor” in terms of accurately identifying recurrence in patients with stage I cancer (Marchetti et al., 2020).

In contrast, (Arnot et al., 2021) investigated the 31-GEP’s ability to predict outcomes in patients with primary cutaneous melanoma referred for sentinel node biopsy. The authors determined that the results of the 31-GEP (either “class 1”, low risk, or “class 2”, high risk) correlated with Breslow thickness, T stage, and SNB positivity, which were significantly higher in class 2 (high risk) patients. Further, classification by way of 31-GEP was predictive of relapse-free survival and distant metastasis-free survival. The authors therefore concluded that the 31-GEP may add useful prognostic information for patients with a diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma undergoing sentinel node biopsy (Arnot et al., 2021).

Kangas-Dick et al. (2021) evaluated the DecisionDx-Melanoma assay in a retrospective chart review of patients at a large cancer institute. 361 patients’ data were analyzed, and a follow-up period median of 15 months was established. First, sentinel node biopsy was performed for 75.9% of the patients, of which, 19.4% tested positive for recurrent cancer. Authors considered GEP class 2B status and noted that it was “significantly associated” with recurrence-free survival (RFS) and distant metastasis-free survival (MDFS) in a univariate analysis. The authors concluded that “genetic profiling of cutaneous melanoma can assist in predicting recurrence and help determine the need for close surveillance. However, traditional pathologic factors remain the strongest independent predictors of recurrence risk.” (Kangas-Dick et al., 2021)

In another study aimed at optimizing the reclassification of patients who may benefit from SLNB, Whitman et al. (2021) integrated the 31-GEP score with certain clinicopathologic features and validated the new algorithm using an independent cohort of 1,674 patients. The integrated 31-GEP (i31-GEP) was able to reclassify a total of 63% of individuals as having either < 5% or > 10% likelihood of positive SLN; which by current guidelines, may allow a more definitive decision about whether to perform SLNB. Further, the i31-GEP demonstrated a negative predictive value (NPV) of 98% in the reclassification of patients with T1 tumors originally classified with a likelihood of SLN positivity of 5% – 10% (Whitman et al., 2021).

CP-GEP (Merlin Assay) (SkylineDx)

An 8-gene expression profile test called CP [clinicopathologic]-GEP was developed to help identify patients who might safely avoid SLNB through reclassification of their risk of nodal metastasis to < 5%. In considering certain CP variables, the developers determined that Breslow thickness and patient age were sufficiently predictive of the risk of SLN metastasis. Double-loop cross-validation [DLCV] and least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) further identified several genes that distinguished between patients with positive and negative SLNB results. Ultimately, 8 genes (MLANA, GDF15, CXCL8, LOXL4, TGFBR1, ITGB3, PLAT, and SERPINE2) along with the 2 CP variables (Breslow thickness and patient age) completed the CP-GEP model.

The CP-GEP model was tested in a cohort of 754 patients diagnosed with cutaneous melanoma, who underwent SLNB within 90 days of their diagnosis. The validity of the model changed based on different T categories of melanoma and demonstrated increasingly higher sensitivity with increasing T category. An inverse relationship was observed between specificity and T category. Theoretically, the model could have reduced the SNLB rate in T1b patients by 80%, though the rate reduction dropped as the T category increased across the patient population. The negative predictive value was 91% or higher across all T categories (Bellomo et al., 2020).

The CP-GEP model was independently validated by Yousaf et al. (2021) in a separate cohort of 208 adult patients with primary cutaneous melanoma and confirmed the trends originally published by Bellomo et al. (2020). As the T category of melanomas increased, the sensitivity of the model sequentially increased, while the specificity decreased. The highest SLNB reduction rates were observed in lower T category patients (T1), and an NPV of at least 93.3% was observed across all T categories in the study. Importantly, the model was further validated focusing only on patients 65 years of age or older, as the incidence of melanoma is greater in older patient populations. Similar results were obtained compared to the full patient cohort, demonstrating the applicability of the model across all age ranges included in the study (Yousaf et al., 2021).

11-GEP (Melagenix) (NeraCare)

Another GEP test was developed to better define the probability of patient survival at the time of first diagnosis. 11 prognostically-relevant genes previously identified through whole-transcriptome analysis (Brunner et al., 2013) of fresh-frozen melanomas were evaluated (KRT9, DCD, PIP, SCGB1D2, SCGB2A2, COL6A6, GBP4, KLHL41, ECRG2, HES6, and MUC7), and 8 of these were found to be statistically significantly associated with melanoma-specific survival (all but ECRG2, HES6, and MUC7). Based on the coded expression data of the 8 significantly associated genes, a binary GEP “score” of either 0 or 1 was generated, representing “low risk” or “high risk,” respectively.

To validate the GEP score, inter-assay variability was examined across 4 different laboratories. Concordance was high between replicates, with 93% of replicate determinations confirming the score. Next, the GEP score was challenged with a cohort of 211 melanomas whose prognostic assessment was erroneous by AJCC staging alone, where the test discriminated successfully between short-term and long-term survivors (Brunner et al., 2018).

An investigation by Amaral et al. (2020) supported the clinical validity of the Melagenix test (referred to in this study as the 11-gene expression profiling score [GEPS]). GEPS was calculated for 245 patients diagnosed with stage II cutaneous melanoma, and the scores were determined to be either “high” (median: 1.06) or “low” (median: –0.21). A significant difference in melanoma-specific survival, distant metastasis free survival, and relapse-free survival was confirmed between high-score and low-score patients. Similarly, Gambichler et al. (2021) used the 11-GEP test to determine whether a high or low score correlated with melanoma-specific survival. The authors documented decreasing probability of melanoma-specific survival with increasing 11-GEP scores. The authors further concluded that the 11-GEP is capable of identifying patients with 10-year survival probabilities above 90% (Gambichler et al., 2021).

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network

The NCCN Melanoma Panel strongly recommends testing for and reporting the presence or absence of BRAF and KIT gene mutations that may impact treatment options in patients with metastatic melanoma (stage IV patients); this testing is only recommended for patients with advanced disease for whom molecular targeted therapies could be beneficial (NCCN, 2022). The guidelines state that “if BRAF single-gene testing was the initial test performed, and is negative, clinicians should strongly consider larger NGS panels to identify other potential genetic targets” such as KIT. In addition, “Mutational analysis for BRAF or multigene testing of the primary lesion is not recommended for patients with cutaneous melanoma unless required to guide adjuvant or other systemic therapy or consideration of clinical trials” (NCCN, 2022). The panel also states, “The use of gene expression profiling (GEP) testing according to specific AJCC-8 melanoma stage (before or after sentinel lymph node biopsy [SLNB]) requires further prospective investigation in large, contemporary data sets of unselected patients. Prognostic GEP testing to differentiate melanomas at low versus high risk for metastasis should not replace pathologic staging procedures. Moreover, since there is a low probability of metastasis in stage I melanoma and higher proportion of false-positive results, GEP testing should not guide clinical decision-making in this subgroup.” The guidelines explicitly note that “currently available GEP tests should not be used to determine SLNB eligibility” (NCCN, 2022). Finally, the NCCN declared that “BRAF mutation testing is recommended for patients with stage III [melanoma] at high risk for recurrence for whom future BRAF-directed therapy may be an option (NCCN, 2022).” Importantly, the NCCN remarks that “repeat molecular testing upon recurrence or metastasis is likely to be of low yield, unless new or more comprehensive testing methods are used or a larger, more representative sample is available if concern for sampling error.”

The NCCN also recognizes NRAS as a relevant mutation for melanoma, noting that NRAS mutations are present in “approximately 15% of melanomas with chronic and intermittent sun exposure, acral surfaces, and mucosal surfaces”. Due to the low probability of overlapping targetable mutations (such as BRAF or KIT), the NCCN remarks that “the presence of an NRAS mutation may identify patients who will not benefit from additional molecular testing” (NCCN, 2022).

Regarding GEP testing, the NCCN recognizes this methodology as a potentially helpful tool to detect melanocytic neoplasms following histopathology. With respect to prognostic testing, the NCCN states that “Commercially available GEP tests are marketed as being able to classify cutaneous melanoma into separate categories based on risk of metastasis. However, it remains unclear whether these GEP platforms provide clinically actionable prognostic information when used in addition to or in comparison with known clinicopathologic factors or multivariate nomograms that incorporate patient sex, age, tumor location and thickness, ulceration, mitotic rate, lymphovascular invasion, microsatellites, and/or SLNB status. Furthermore, the impact of these tests on treatment recommendations has not been established.” The NCCN continues by stating that even though several studies have been published highlighting the prognostic capabilities of GEP tests, f “It remains unclear whether available GEP tests are reliably predictive of outcome across the risk spectrum of melanoma” (NCCN, 2022). Apart from prognostication, the NCCN states that “Pre-diagnostic noninvasive patch testing may also be helpful to guide biopsy decisions” (NCCN, 2022).

The American Academy of Dermatology (AAD)

The AAD recently published guidelines for the care and management of primary cutaneous melanoma. Regarding skin biopsies, the AAD states that while many different molecular and imaging techniques have been developed, “skin biopsy remains the first step to establish a definitive diagnosis of CM [cutaneous melanoma]”; further, the guidelines also state that “Newer noninvasive techniques (e.g., reflectance confocal microscopy [RCM], as well as electrical impedance spectroscopy, gene expression analysis, optical coherence tomography, and others [see the section Emerging Diagnostic Technologies]) can also be considered as these become more readily available” (Swetter et al., 2019).

The AAD notes that these guidelines highlight several gaps in research including “the clinical utility and prognostic significance of various biomarkers and molecular tests; optimal clinical situations in which to pursue multigene somatic and germline mutational analysis; and the value of ancillary molecular tests in comparison with well-established clinicopathologic predictors of outcome” (Swetter et al., 2019). it is then noted that “Efforts to standardize the histopathologic diagnosis and categorization of melanocytic neoplasms are under way to reduce the significant interobserver variability among pathologists. Ongoing advances in genomic medicine may make many of the aforementioned issues obsolete before the next AAD melanoma CPG is issued” (Swetter et al., 2019).

Regarding patients with a family history of invasive cutaneous melanoma (at least 3 affected members on 1 side of the family), “Cancer risk counseling by a qualified genetic counselor is recommended” (Swetter et al., 2019).

Finally, the AAD states “There is insufficient evidence to recommend routine molecular profiling assessment for baseline prognostication. Evidence is lacking that molecular classification should be used to alter patient management outside of current guidelines (e.g., NCCN and AAD). The criteria for and the utility of prognostic molecular testing, including GEP, in aiding clinical decision making (eg. SLNB eligibility, surveillance intensity, and/or therapeutic choice) needs to be evaluated in the context of clinical study or trial” (Swetter et al., 2019).

European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO)

The ESMO has stated that “testing for actionable mutations is mandatory in patients with resectable or unresectable stage III or stage IV [melanoma] [I, A], and is highly recommended in high-risk resected disease stage IIC but not for stage I or stage IIA – IIB. BRAF testing is mandatory [I, A]. If the tumour is BRAF wild type (WT) at the V600 locus (Class I BRAF mutant) sequencing the loci of the other known minor BRAF mutations (Class II and Class III BRAF mutant) to confirm WT status and testing for NRAS and c-kit mutations are recommended [II, C].” Additionally, “patients with metastatic melanoma should have metastasis (preferably) or the primary tumour screened for detection of BRAF V600 mutation treatment options for the first- and second-line settings include anti-PD-1 antibodies (pembrolizumab, nivolumab), PD-1 and ipilimumab for all patients, and BRAFi/MEKi combination for patients with BRAF-mutated melanoma [II, B]” (ESMO, 2019).

American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC)

The AJCC did not include any mention of genetic testing in the most recent 8th edition guidance on melanoma staging, though the authors do highlight that molecularly targeted antitumor therapies such as BRAF inhibitors are now in widespread clinical use (Gershenwald et al., 2017).

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)

The USPSTF examined the utility of visual skin examination for the prevention of melanoma and found that “Only limited evidence was identified for skin cancer screening, particularly regarding potential benefit of skin cancer screening on melanoma mortality” (Wernli et al., 2016). The use of genetic tests in screening for melanoma is not mentioned.

American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO)

The ASCO expert panel recommends needle biopsy as the preferred diagnostic approach to clinically detected lymphadenopathy in any patient with known or suspected metastatic melanoma in regional nodes. Excisional biopsy, a more invasive approach, is not routinely required for diagnosis or characterization of melanoma. The Expert Panel recommends that BRAF mutation testing should be performed at time of diagnosis, but clinicians are not required to wait for the results of that testing if the decision has been made to initiate immunotherapy. If prior testing resulted in a false negative, the panel states that re-testing RAF status upon progression could be considered, but it would not be of value as the panel is not aware of data that supports re-testing. Regarding immunohistochemistry, the panel states “Immunohistochemistry for the BRAF V600E mutation has the most rapid turnaround time; however, less common mutations may be found with other methodologies such as BRAF gene sequencing.” Beyond BRAF testing though, the Expert Panel did not make formal recommendations about other genetic testing (e.g., NRAS and KIT), given insufficient data regarding the efficacy of inhibitors targeting these pathways (Seth et al., 2020).

The ASCO notes that some cancer treatments most commonly used in metastatic melanoma patients (e.g., BRAF inhibitors) may increase the risk of secondary skin cancers; hence, clinicians should be aware of this potential adverse effect when considering such therapeutic agents (Alberg et al., 2020).

European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of DermatoOncology (EADO), and the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC)

A panel of experts from EDF, EADO, and EORTC recommend that BRAF mutation testing be required “in patients with distant metastasis or non-resectable regional metastasis to identify those who are eligible to receive treatment with combined BRAF and MEK inhibitors, and in resected high-risk stage III melanoma patients in the adjuvant setting” (Garbe et al., 2020). Mutational analysis should be performed on metastatic tissue, either distant or regional, or on the primary tumor if metastatic tissue is not feasible. Though there may be a discrepancy rate in the BRAF status between the primary versus metastatic melanoma lesions, the authors note that there is “a high concordance rate in the BRAF status … between primary and metastatic melanoma lesions” (Garbe et al., 2022). Regarding next generation sequencing, the panel claims that it may help in identifying genetic alterations and, when limited to currently actionable genes like BRAF, NRAS, and KIT in a single experiment, may be cost and time effective in the clinical setting (Garbe et al., 2022).

The guideline also commented on NRAS, stating that NRAS mutations are present in 15-20% of melanoma cases and are almost always mutually exclusive with BRAF mutations. The guideline remarked that NRAS status may inform clinicians regarding the BRAF status, although NRAS-based treatments are still under investigation.

Regarding c-KIT, the guideline states that acral and mucosal melanomas should initially be tested for BRAF and NRAS mutations; if both genes were found to be wild-type, the sample should be tested for c-KIT (Garbe et al., 2020).

Tumor mutational burden (TMB) is highlighted in the guideline as a predictive tool for response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in melanoma. The panel recognized a study that demonstrated the positive association of a high TMB value with response and overall survival of melanoma patients treated with a combination of ipilimumab and nivolumab (Forschner et al., 2019).

Finally, the guideline comments on GEP tests like DecisionDx-Melanoma™ and their increased use by clinicians. While a growing pool of literature describes the potential application of GEP tests in the management of various cancers, the authors state “additional data are required in melanoma to address if they provide independent prognostic information in addition to known clinicopathologic factors before they can be integrated into clinical decision-making” (Garbe et al., 2022).

Melanoma Prevention Working Group (MPWG)

This Working Group published a guideline regarding prognostic gene expression profile [GEP] testing for cutaneous melanoma. Although the Group is “optimistic” about the future use of prognostic GEP testing to “improve risk stratification and enhance clinical decision-making”, it states that “more evidence is needed to support GEP testing to inform recommendations regarding SLNB [sentinel lymph node biopsy], intensity of follow-up or imaging surveillance, and postoperative adjuvant therapy.” Overall, the Group remarks that “there are insufficient data to support routine use of currently available prognostic GEP tests to inform management of patients with CM [cutaneous melanoma]” (Grossman et al., 2020).

Skin Cancer Prevention Working Group (SCPWG)

An expert consensus on the appropriate use of prognostic gene expression profiling tests for the management of cutaneous melanoma was published in 2022. The SCPWG reviewed literature for DecisionDx-Melanoma, the 11-GEP (Melagenix) test by NeraCare, and the 8-GEP (CP-GEP; Merlin Assay) by SkylineDx. The eight-person consensus panel of dermatologists unanimously agreed that:

- “Gene expression profile (GEP) tests are validated, reproducible, and consistent across studies;

- Integrating GEPs into AJCC8 and NCCN models can improve prognostic accuracy;

- Prognostic GEP tests can inform clinical decision making regarding sentinel lymph node biopsies;

- Incorporating GEPs into real-world clinical management has positively impacted patient outcomes”

Additionally, 7 out of 8 panelists agreed that “the AJCC8 and NCCN prognostic model, which does not account for genomic expression, may not optimize melanoma prognostic assessment” (Farberg et al., 2022).

The National Society for Cutaneous Medicine (NSCM)

An expert panel gathered to develop consensus-based guidelines on the appropriate use criteria for the integration of diagnostic and prognostic GEP assays into the management of cutaneous malignant melanoma. These guidelines include recommendations for the 2-GEP test (DermTech PLA), the 23-GEP test (myPath®), and the 31-GEP test (DecisionDx-Melanoma). Regarding use of the 31-GEP test, a total of 14 recommendations were considered:

A-strength recommendation:

- “Use of the 31-GEP test to aid in the management of patients who are SLNBx negative”

B-strength recommendation:

- “Integration of 31-GEP results into the decision to adjust follow-up frequency

- Integration of 31-GEP results into the decision to order adjunctive imaging studies

- Integration of 31-GEP results into management of patients with T1a tumors with Breslow depth <0.8 mm and other adverse prognostic factors

- Integration of 31-GEP results into management of patients with T1 or T2 tumors who are sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNBx) eligible

- Integration of 31-GEP results into management of patients with T1b tumors

- Integration of 31-GEP results into management of patients with T2 tumors

- Integration of 31-GEP results into management of patients with a low-risk category based on traditional AJCC factors”

C-strength recommendation:

- “Integration of 31-GEP results into the assessment of prognosis and management options for patients with T1a tumors with a positive deep margin

- Integration of 31-GEP results into the assessment of prognosis and management options for patients with T1b tumors with a positive deep margin

- Integration of 31-GEP results to for risk-stratification of patients in clinical trials

- Use of 31-GEP results as a criterion for eligibility for a chemotherapy regimen

- T4 disease as a contraindication for use of the 31-GEP test

- Melanoma in situ as a contraindication for use of the 31-GEP test”

7 recommendations for use of the 2-GEP test were considered as follows:

B-strength recommendation:

- “Cases in which patients present with atypical lesions requiring additional assessment beyond inspection in order to aid in the biopsy decision”

C-strength recommendations:

- Cases in which patients refuse surgical biopsy

- Cases in which suspicious lesions present in cosmetically sensitive areas

- Cases in which patients have undergone numerous biopsies in the past and wish to avoid additional biopsy procedures

- Scenarios in which patients have a relative contraindication to surgical biopsy

- Patients with increased risk of infection (e.g., immunosuppressed patients)

- Patients with heightened risk of poor wound healing

Expert consensus was reached on 8 recommendations for use of the 23-GEP test:

A-strength recommendation:

- “Differentiation of a nevus from melanoma in an adult patient when the morphologic findings are ambiguous by light microscopic parameters”

B-strength recommendations:

- “Cases with pathology suggestive or suspicious for nevoid melanoma vs. benign melanocytic nevus

- Cases with pathology suggestive or suspicious for atypical Spitz tumor vs. Spitzoid melanoma

- Instances in which pathology is suggestive of or suspicious for severely atypical compound melanocytic proliferation vs melanoma on cosmetically sensitive areas”

C-strength recommendations:

- “Instances of pathology suggestive or suspicious for melanoma arising from within a severely dysplastic nevus

- Cases of pathology suggestive or suspicious for benign vs. malignant blue nevus

- To differentiate suspicious lesions in low-risk populations

- Upon request from the referring dermatologist following an ambiguous pathology report” (Berman et al., 2019)