Identification of Microorganisms Using Nucleic Acid Probes - CAM 303

Description

Nucleic acid hybridization technologies utilize complementary properties of the DNA double-helix structures to anneal together DNA fragments from different sources. These techniques are utilized in polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and fluorescent resonance energy transfer (FRET) techniques to identify microorganisms (Khan, 2014).

Regulatory Status

As of May 11, 2020, a list of current U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA, 2020) approved or cleared nucleic acid-based microbial tests is available at: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/vitro-diagnostics/nucleic-acid-based-tests..

Policy

-

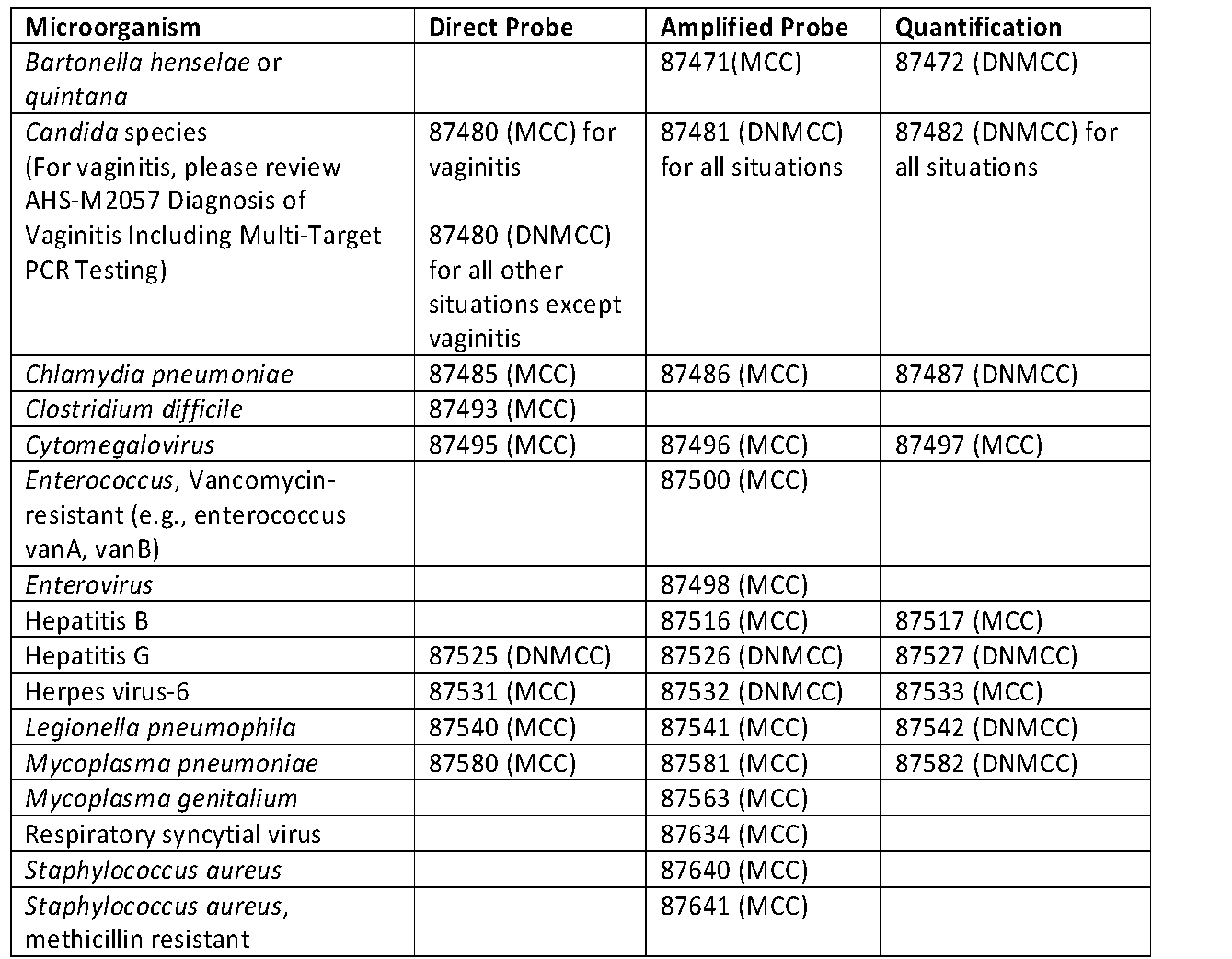

The status of nucleic acid identification using direct probe, amplified probe, or quantification for the microorganism’s procedure codes is summarized in Table 1 below. "MCC" in the table below indicates that the test is considered MEDICALLY NECESSARY; while “DNMCC” tests indicates that the test is considered NOT MEDICALLY NECESSARY.

- The technique for quantification includes both amplification and direct probes; therefore, simultaneous coding for both amplification or direct probes is considered NOT MEDICALLY NECESSARY.

- PCR testing for the following microorganisms that do not have specific CPT codes is considered MEDICALLY NECESSARY (not an all-inclusive list):

- Actinomyces, for identification of actinomyces species in tissue specimens

- Adenovirus, to diagnose adenovirus myocarditis, and to diagnose adenovirus infection in immunocompromised hosts, including transplant recipients

- Bacillus Anthracis

- BK polyomavirus in transplant recipients receiving immunosuppressive therapies and persons with immunosuppressive diseases

- Bordetella pertussis and B. parapertussis, for diagnosis of whooping cough in individuals with coughing

- Brucella spp., for members with signs and symptoms of Brucellosis, and history of direct contact with infected animals and their carcasses or secretions or by ingesting unpasteurized milk or milk products

- Burkholderia infections (including B. cepacia, B. gladioli), diagnosis

- Chancroid (Haemophilus ducreyi), for diagnosis of persons with genital ulcer disease

- Coxiella burnetii, for confirmation of acute Q fever

- EBOLA

- Epidemic typhus (Rickettsia prowazekii), diagnosis

- Epstein Barr Virus (EBV): for detection of EBV in post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder; or for testing for EBV in persons with lymphoma; or for those who are immunocompromised for other reasons.

- Francisella tularensis, for presumptive diagnosis of tularemia

- Hantavirus, diagnosis

- Hemorrhagic fevers and related syndromes caused by viruses of the family Bunyaviridae (Rift Valley fever, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, hemorrhagic fever with renal syndromes), for diagnosis in acute phase in persons with clinical presentation suggestive of these conditions

- Hepatitis D virus, for confirmation of active infection in persons with anti-HDV antibodies

- Hepatitis E virus, for definitive diagnosis in persons with anti-HEV antibodies

- Human T Lymphotropic Virus type 1 and type 2 (HTLV-I and HTLV-II), to confirm the presence of HTLV-I and HTLV-II in the cerebrospinal fluid of persons with signs or symptoms of HTLV-I/HTLV-II

- Human metapneumovirus

- JC polyomavirus, in transplant recipients receiving immunosuppressive therapies, in persons with immunosuppressive diseases, and for diagnosing progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in persons with multiple sclerosis or Crohn's disease receiving natalizumab (Tysabri)

- Leishmaniasis, diagnosis

- Measles virus (Morbilliviruses), for diagnosis of measles

- Mumps

- Neisseria meningitidis, to establish diagnosis where antibiotics have been started before cultures have been obtained

- Parvovirus, for detecting chronic infection in immunocompromised persons

- Psittacosis, for diagnosis of Chlamydophila (Chlamydia) psittaci infection

- Rubella, diagnosis

- Toxoplasma gondii, for detection of T. gondii infection in immunocompromised persons with signs and symptoms of toxoplasmosis, and for detection of congenital Toxoplasma gondii infection (including testing of amniotic fluid for toxoplasma infection)

- Varicella-Zoster infections

- Whipple's disease (T. whippeli), biopsy tissue from small bowel, abdominal or peripheral lymph nodes, or other organs of persons with signs and symptoms, to establish the diagnosis

- Yersinia Pestis

Policy Guidelines

A discussion of every infectious agent that might be detected with a probe technique is beyond the scope of this policy. Many probes have been combined into panels of tests. For the purposes of this policy, other than the respiratory virus panel, only individual probes are reviewed.

Table of Terminology

|

Term |

Definition |

|

AMA |

American Medical Association |

|

CDC |

Centers of Disease Control and Prevention |

|

CIDT |

Culture-independent diagnostic test |

|

CMV |

Cytomegalovirus |

|

CPT |

Current procedural terminology |

|

DFA |

Direct fluorescent antibody testing |

|

DNA |

Deoxyribonucleic acid |

|

DNMCC |

Does not meet coverage criteria |

|

EBV |

Epstein Barr virus |

|

EVD |

Ebola virus disease |

|

FDA |

Food and Drug Administration |

|

FRET |

Fluorescent resonance energy transfer |

|

H5N1 |

Hemagglutinin type 5 and neuraminidase type 1 (Avian Influenza A) |

|

HDV |

Hepatitis D virus |

|

HEV |

Hepatitis E virus |

|

HIV 1 |

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 |

|

HIV 2 |

Human immunodeficiency virus type 2 |

|

HPV |

Human papillomavirus |

|

HSV |

Herpes simplex virus |

|

HTLV-I |

Human t lymphotropic virus type 1 |

|

HTLV-II |

Human t lymphotropic virus type 2 |

|

IDSA |

Infectious Diseases Society of America |

|

ITS |

Internal transcribed region |

|

MCC |

Meets coverage criteria |

|

MRSA |

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus |

|

NAATs |

Nucleic acid amplification tests |

|

NGU |

Nongonococcal urethritis |

|

PCR |

Polymerase chain reaction |

|

PID |

Pelvic inflammatory disease |

|

qPCR |

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

|

rDNA |

Recombinant deoxyribonucleic acid |

|

RNA |

Ribonucleic acid |

|

rRT-PCR |

Real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction |

|

RSV |

Respiratory syncytial virus infection |

|

RT-PCR |

Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction |

|

SARS |

Severe acute respiratory syndrome |

Rationale

Nucleic acid hybridization technologies, including polymerase chain reaction (PCR), ligase- or helicase-dependent amplification, and transcription-mediated amplification, are beneficial tools for pathogen detection in blood culture and other clinical specimens due to high specificity and sensitivity (Khan, 2014). The use of nucleic acid-based methods to detect bacterial pathogens in a clinical laboratory setting offers “increased sensitivity and specificity over traditional microbiological techniques” due to its specificity, sensitivity, reduction in time, and high-throughput capability; however, “contamination potential, lack of standardization or validation for some assays, complex interpretation of results, and increased cost are possible limitations of these tests” (Mothershed & Whitney, 2006).

2018 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA)

Specific guidelines for testing of many organisms listed within the policy coverage criteria is found in the updated 2018 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines and recommendations titled, “A Guide to Utilization of the Microbiology Laboratory for Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases: 2018 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Society for Microbiology” (Miller et al., 2018). “This document is organized by body system, although many organisms are capable of causing disease in > 1 body system. There may be a redundant mention of some organisms because of their propensity to infect multiple sites. One of the unique features of this document is its ability to assist clinicians who have specific suspicions regarding possible etiologic agents causing a specific type of disease. When the term “clinician” is used throughout the document, it also includes other licensed, advanced practice providers. Another unique feature is that in most chapters, there are targeted recommendations and precautions regarding selecting and collecting specimens for analysis for a disease process. It is very easy to access critical information about a specific body site just by consulting the table of contents. Within each chapter, there is a table describing the specimen needs regarding a variety of etiologic agents that one may suspect as causing the illness. The test methods in the tables are listed in priority order according to the recommendations of the authors and reviewers” (Miller et al., 2018).

Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

MRSA

The CDC remarks that nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs, such as PCR) “can be used for direct detection of mecA, the most common gene mediating oxacillin resistance in staphylococci,” but will not detect novel resistance mechanisms or uncommon phenotypes (CDC, 2019b).

Candida Auris (C. auris)

The CDC writes that “Molecular methods based on sequencing the D1-D2 region of the 28s rDNA or the Internal Transcribed Region (ITS) of rDNA also can identify C. auris.” The CDC further notes that various PCR methods have been developed for identifying C. auris (CDC, 2020a).

Chlamydia Pneumoniae (C. pneumoniae)

The CDC writes that RT-PCR is the “preferred” method of detecting an acute C. pneumoniae infection. The CDC further notes that a positive culture should be confirmed by a second test, such as PCR (CDC, 2021a).

Ebola

The CDC states that for diagnosis of Ebola, “There must be a combination of symptoms suggestive of EVD AND a possible exposure to EVD within 21 days before the onset of symptoms.” The CDC notes that PCR is one of the most common diagnostic methods (CDC, 2019a).

Salmonella

The CDC writes that diagnosis requires detection of the Salmonella bacteria, be it through culture or a “culture-independent diagnostic test (CIDT)” (CDC, 2019c).

Giardia

The CDC states that microscopy with direct fluorescent antibody testing (DFA) is considered the test of choice for diagnosing giardiasis, but rapid immunochromatographic cartridge assays, enzyme immunoassay kits, microscopy with trichrome staining, and molecular assays may be alternatively used as well. To obtain more accurate test results, the CDC recommends collecting three stool specimens from patients over the course of a few days. But, only molecular testing (e.g., DNA sequencing) can identify Giardia strains (CDC, 2021c).

Non-Polio Enterovirus

The CDC remarks that their laboratories “routinely” perform qualitative testing for enteroviruses, parechoviruses, and uncommon picornaviruses (CDC, 2018).

Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV)

The CDC writes that real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) and antigen detection tests are the most commonly used diagnostic tests, and are effective in infants and young children. However, the highly sensitive rRT-PCR is recommended to be used when testing older children and adults with RSV (CDC, 2020c).

Mycoplasma Genitalium

The CDC writes that “Men with recurrent NGU [nongonococcal urethritis] should be tested for M. genitalium using an FDA-cleared NAAT. If resistance testing is available, it should be performed and the results used to guide therapy. Women with recurrent cervicitis should be tested for M. genitalium, and testing should be considered among women with PID [pelvic inflammatory disease]. Testing should be accompanied with resistance testing, if available. Screening of asymptomatic M. genitalium infection among women and men or extragenital testing for M. genitalium is not recommended. In clinical practice, if testing is unavailable, M. genitalium should be suspected in cases of persistent or recurrent urethritis or cervicitis and considered for PID” (CDC, 2021d).

Miscellaneous

The CDC does not mention the need to quantify [through PCR] Bartonella, Legionella pneumophila, or Mycoplasma pneumoniae. However, PCR can be performed for both Legionella pneumophila and Mycoplasma pneumoniae specimen (CDC, 2020b, 2021b, 2022). No guidance was found on Hepatitis G.

Committee on Infectious Diseases, American Academy of Pediatrics, 31st Edition (2018-2021, Red Book)

The Committee on Infectious Diseases released joint guidelines with the American Academy of Pediatrics. In it, they note that “the presumptive diagnosis of mucocutaneous candidiasis or thrush usually can be made clinically.” They also state that FISH probes may rapidly detect Candida species from positive blood culture samples, although PCR assays have also been developed for this purpose (Pediatrics, 2018).

References:

- CDC. (2018, November 14). Non-Polio Enterovirus, CDC Laboratory Testing & Procedures. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/non-polio-enterovirus/lab-testing/testing-procedures.html

- CDC. (2019a, November 5). Ebola (Ebola Virus Disease), Diagnosis. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/diagnosis/index.html

- CDC. (2019b, February 6). Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Laboratory Testing. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mrsa/lab/index.html#anchor_1548439781

- CDC. (2019c, December 5). Salmonella, Diagnostic and Public Health Testing. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/general/diagnosis-treatment.html

- CDC. (2020a, May 29). Identification of Candida auris. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/candida-auris/identification.html

- CDC. (2020b, June 5). Mycoplasma pneumoniae Infections - Diagnostic methods Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/pneumonia/atypical/mycoplasma/hcp/diagnostic-methods.html

- CDC. (2020c, December 18). Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection (RSV), For Healthcare Professionals. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/rsv/clinical/index.html#lab

- CDC. (2021a, November 15). Chlamydia pneumoniae Infection, Diagnostic Methods. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/pneumonia/atypical/cpneumoniae/hcp/diagnostic.html

- CDC. (2021b, March 25). Legionella (Legionnaires' Disease and Pontiac Fever) - Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/legionella/clinicians/diagnostic-testing.html

- CDC. (2021c, March 1). Parasites - Giardia for Medical Professionals. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/giardia/medical-professionals.html

- CDC. (2021d, July 22). Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines, 2021. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/mycoplasmagenitalium.htm

- CDC. (2022, January 10). Bartonella Infection. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/bartonella/bartonella-henselae/index.html

- FDA. (2022, April 19). Nucleic Acid Based Tests. Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/vitro-diagnostics/nucleic-acid-based-tests

- Khan, A. (2014). Rapid Advances in Nucleic Acid Technologies for Detection and Diagnostics of Pathogens. J Microbiol Exp, 1(2). doi:10.15406/jmen.2014.01.00009

- Miller, J. M., Binnicker, M. J., Campbell, S., Carroll, K. C., Chapin, K. C., Gilligan, P. H., . . . Yao, J. D. (2018). A Guide to Utilization of the Microbiology Laboratory for Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases: 2018 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Society for Microbiology. Clinical Infectious Diseases, ciy381-ciy381. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy381

- Mothershed, E. A., & Whitney, A. M. (2006). Nucleic acid-based methods for the detection of bacterial pathogens: present and future considerations for the clinical laboratory. Clin Chim Acta, 363(1-2), 206-220. doi:10.1016/j.cccn.2005.05.050

- Pediatrics, C. o. I. D. A. A. o. (2018). Red Book® 2018.

Coding Section

|

Code |

Number |

Description |

|

CPT |

87471 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); Bartonella henselae and Bartonella quintana, amplified probe technique |

|

|

87472 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); Bartonella henselae and Bartonella quintana, quantification |

|

|

87480 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); Candida species, direct probe technique |

|

|

87481 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); Candida species, amplified probe technique |

|

|

87482 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); Candida species, quantification |

|

|

87485 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); Chlamydia pneumoniae, direct probe technique |

|

|

87486 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); Chlamydia pneumoniae, amplified probe technique |

|

|

87487 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); Chlamydia pneumoniae, quantification |

|

|

87493 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); Clostridium difficile, toxin gene(s), amplified probe technique |

|

|

87495 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); cytomegalovirus, direct probe technique |

|

|

87496 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); cytomegalovirus, amplified probe technique |

|

|

87497 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); cytomegalovirus, quantification |

|

|

87498 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); enterovirus, amplified probe technique, includes reverse transcription when performed |

|

|

87500 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); vancomycin resistance (e.g., enterococcus species van A, van B), amplified probe technique |

|

|

87516 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); hepatitis B virus, amplified probe technique |

|

|

87517 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); hepatitis B virus, quantification |

|

|

87525 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); hepatitis G, direct probe technique |

|

|

87526 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); hepatitis G, amplified probe technique |

|

|

87527 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); hepatitis G, quantification |

|

|

87531 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); Herpes virus-6, direct probe technique |

|

|

87532 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); Herpes virus-6, amplified probe technique |

|

|

87533 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); Herpes virus-6, quantification |

|

|

87540 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); Legionella pneumophila, direct probe technique |

|

|

87541 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); Legionella pneumophila, amplified probe technique |

|

|

87542 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); Legionella pneumophila, quantification |

|

|

87563 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); Mycoplasma genitalium, amplified probe technique |

|

|

87580 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); Mycoplasma pneumoniae, direct probe technique |

|

|

87581 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); Mycoplasma pneumoniae, amplified probe technique |

|

|

87582 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); Mycoplasma pneumoniae, quantification |

|

|

87634 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); respiratory syncytial virus, amplified probe technique |

|

|

87640 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); Staphylococcus aureus, amplified probe technique |

|

|

87641 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); Staphylococcus aureus, methicillin resistant, amplified probe technique |

|

|

87797 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA), not otherwise specified; direct probe technique, each organism |

|

|

87798 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA), not otherwise specified; amplified probe technique, each organism |

|

|

87799 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA), not otherwise specified; quantification, each organism |

Procedure and diagnosis codes on Medical Policy documents are included only as a general reference tool for each policy. They may not be all-inclusive.

This medical policy was developed through consideration of peer-reviewed medical literature generally recognized by the relevant medical community, U.S. FDA approval status, nationally accepted standards of medical practice and accepted standards of medical practice in this community, Blue Cross Blue Shield Association technology assessment program (TEC) and other non-affiliated technology evaluation centers, reference to federal regulations, other plan medical policies, and accredited national guidelines.

"Current Procedural Terminology © American Medical Association. All Rights Reserved"

History From 2014 Forward

| 12/20/2022 | Annual review, no change to policy. Maintaining as written. |

| 07/21/2022 | Annual review, policy rewritten for clarity, no change to policy intent. Updating description, rationale and references. |

|

10/01/2021 |

Interim review updating coverage criteria for 87481 and 87482 related to vaginitis per CDC guidlelines. No other changes made. |

|

07/26/2021 |

Annual review, no change to policy intent. Updating rationale and references. |

|

10/15/2020 |

Interim Review. Correcting policy verbiage on code 87487. No other changes made. |

|

09/24/2020 |

Updating annual review date to 07/2021. No other changes. |

|

07/01/2020 |

Interim review, updating Chlamydia pneumoniae to medically necessary. Also reformatting the policy for clarity. |

|

04/08/2020 |

Interim review to add coverage criteria and coding related to COVID-19. |

|

10/29/2019 |

Annual review, no change to policy intent. Reformatting for clarity. Updating coding. |

|

09/25/2019 |

Corrected formatting. No other changes made. |

|

05/29/2019 |

Corrected typo. No change to policy intent. |

|

11/27/2018 |

Major rewrite of this policy related to adoption of diagnostic testing of most common sexually transmitted infections, B-Hemolytic Streptococcus Testing, and testing for mosquito- or tick-related infections. All four policies will be implemented on 02/01/2019. |

|

12/7/2017 |

Updating policy with 2018 coding. No other changes. |

|

11/28/2017 |

Annual review. Updating background, description, regulatory status, policy, guidelines, references and coding. |

|

04/25/2017 |

Updated category to Laboratory. No other changes. |

|

01/10/2017 |

Annual Review. No significant changes. |

|

11/30/2016 |

Updated coding section with 2017 codes. |

|

05/09/2016 |

Interim review, updating Human herpes virus 6 testing to indicate that direct probe and quantification can be considered medically necessary, but, that amplified probe (87532) is considered investigational. No other changes. |

|

01/21/2015 |

Returning Borrelia burgdorferi as medically necessary with reference to: See policy 50108. |

|

01/05/2016 |

Interim review with the following policy intent changes: Medically necessary statement added for non-quantified nucleic acid-based testing for enterovirus, Legionella pneumophila, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and Bartonella spp, and for quantified testing for human herpesvirus 6. Borrelia, major revision in the visual look of the policy, but, only the content listed has been altered in intent. Updating background, description, guidelines, verbiage, rationale, references, and coding. |

|

11/24/2015 |

Annual review, no changes made. |

|

3/16/2015 |

Removed the word "archived" in table 1 on Candida species, Gardnerella vaginalis and Human Papillomavirus lines. No other changes. |

|

10/27/2014 |

Annual review. Added description and coding. Updated background, policy, rationale and references. New CPT codes (8751xx 1-3 and 876xx 3-5 added. |